Article

Objectification and sexualisation of the Black female body – from Sara Baartman to Beyoncé

Since the 15th century – in the Americas and the colonised world – the Black female body has been seen as a product to be used to produce more products in the same image; this has some parallels with the Black African tradition where the Black female body was viewed as a source of social success and family wealth, the commonality between these two views is patriarchy.

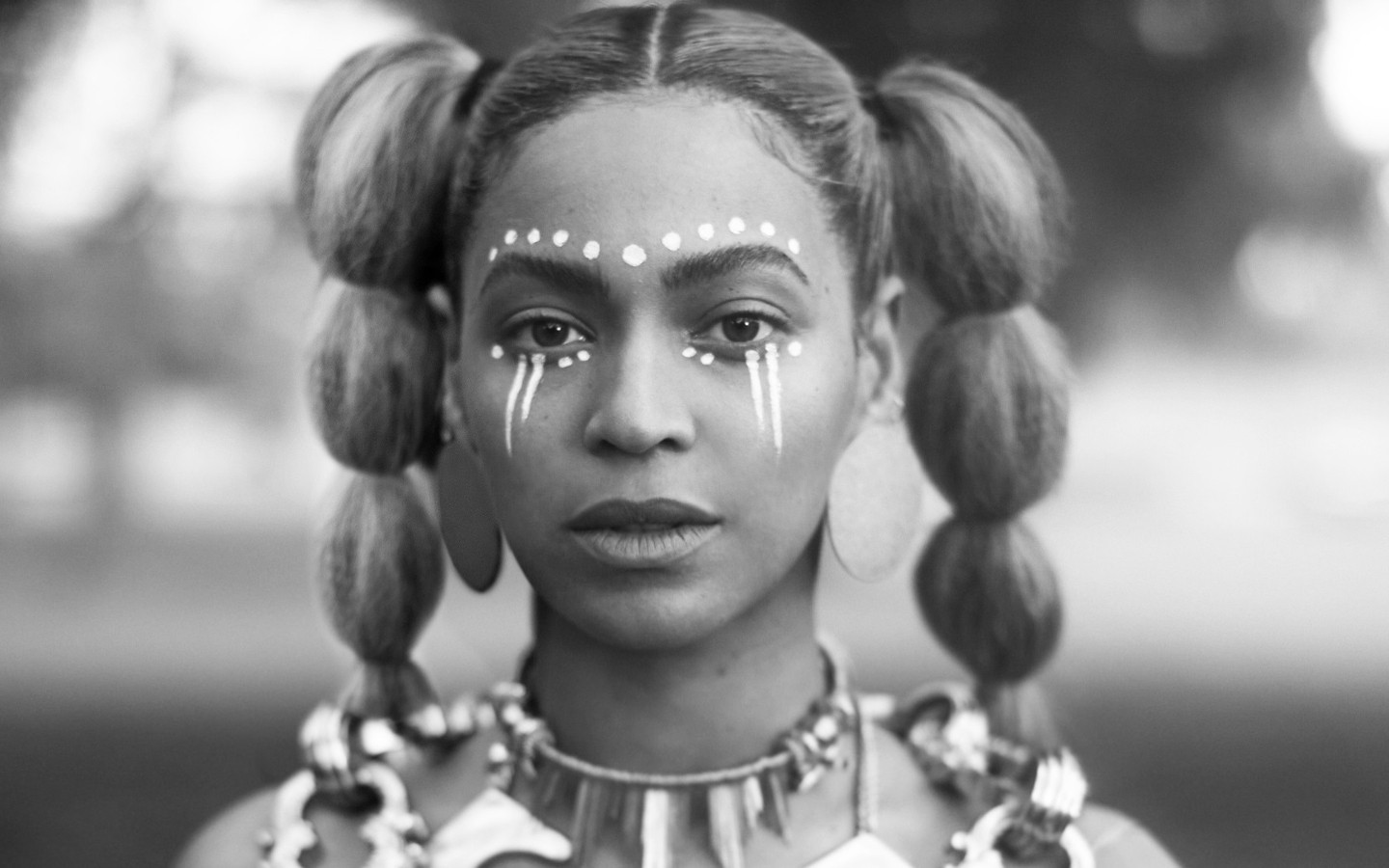

Objectification of the Black female body renders the black woman a commodity that others can enact their will upon, e.g. rage, lust, anger, disgust, desire. Therefore Black women need to regain control of the image that they project of their own bodies. Beyoncé is one Black woman who appears to be controlling the representation and reflection of her concept of the Black female body.

During her performances Beyoncé often uses her body in a sexualised manner as a signifier of her own feminism. Her stage and public appearances contest the whiteness of mainstream feminism, although Dr bell hooks, a black academic feminist, described Beyoncé as a ‘terrorist’ who potentially harms black girls with her sexualised performances (2014).

After the release of Lemonade (2017) hooks also suggested that Beyoncé used that opportunity to exploit “images of Black female bodies” in a way that was neither “radical nor revolutionary” and that it glamorised the gendered dichotomy and “glamorizes a world of gendered cultural paradox and contradiction.”

Black female bodies have historically had repeated collisions with masculinity, power, and whiteness; these bodies constantly exhibit strength beyond the imposed theories as they continue to disrupt the masculine narrative of superiority, because without them Black life does not continue.

When Black bodies were viewed as products they were also categorised as sexual and economic property where the sexuality and reproduction were strictly controlled; in this manner they are systematically dehumanised and positioned to be subject to the white patriarchal system. A prime example of this occurred in 1814 when Sara (aka Sarah or Saartjie) Baartman, also known as the Hottentot Venus, was displayed in a cage, and objectified as a deviant savage who was an inferior being. Baartman was described has having “abnormal sexuality and genitalia”.

Sara Baartman was in fact a Khoikhoi woman – an aboriginal South African – who became a domestic servant to Dutch coloniser Pieter Willem Cezar in Cape Town, South Africa, before she was employed by English ship surgeon William Dunlop and Cezar’s brother Hendrik.

Apparently Sara Baartman signed a contract on 29 October 1810 with the terms stipulating that she would be a domestic servant in England and Ireland for Dunlop and Hendrik Cezar in addition to being exhibited for entertainment purposes. The contract allegedly stated that Baartman would receive a portion of the earnings and would also be allowed to return to South Africa after five years. However, after four years in England Baartman was sold to Reaux, a showman in France, who showcased her alongside his animals.

Baartman died in France in 1815 after being exhibited and studied as a science specimen by French anatomists, zoologists and physiologists. Baartman was used to emphasise the theory that Black Africans were hyper sexual and less human than Europeans. It was through this initial commodification process that black bodies were positioned to be subject to the white patriarchal system. As Iman Cooper (2015) says essentially “the humanity of the black body was ruptured into an object to be bought and sold, in order to satisfy the economic desires of the white slave owners.”

Baartman is symbolic because her Black African female body was used as imagery to represent, reflect and affect the nascent European held opinions of ‘savage sexuality and racial inferiority’ of the time. The physical presence of Black bodies in the world is undeniable, however the concept of racism made the power and self-agency of those bodies incomprehensible and refutable in the eyes of white colonisers, but the black body has always remained self-defining and disruptive to global theories of cultural being.

This originally European social conceptualisation of the black body has remained widely unchallenged by mainstream society, especially in media outlets that are controlled by heteronormative white men. Therein femininity is also codified as Christian, white, docile, chase and pure, while Black women’s religious characteristics are not viewed in the same way as their white counterparts they have historically been viewed as uncontrolled, loud, wild, lewd and evil. Both black and white female bodies have been regulated according to the diametrically opposed assumptions held about each other, largely based on the overriding global standard rooted in racism.

With the exception of talk show hosts such as American Oprah Winfrey and British Trisha Goddard, Black women on television have mainly been represented as “crude stereotypes of exotic animalistic hypersexuality (black women) … or sexual submissiveness (Asian women)” – this is often represented as lacking in ‘feminine’ behaviour. Sexualised women are also frequently depicted as working class – all is dependent on the ‘viewer’s’ gaze. In this instance who is the viewer? Male, white, middle class.

Black women performers like Beyoncé often use their bodies as a means to reclaim and contest the control of the image of the Black female body from their personal perspective: powerful, sexual, self-regulating.

Who is right, Beyoncé or bell hooks? Can’t they both be correct? Black women have a right to control their own image and decide on the sexualisation of their individual bodies – that is their agency and feminist right of self determination.

Bodies will always be sexualised and objectified by the gaze of the ‘other’ be it the gaze of a man or another woman (Black or white). Therefore Black women are justified in deciding their own degree of visual sexualisation according to the pervading and overarching social mores, nevertheless I do not believe sexualisation can be ignored or viewed in isolation without considering the history of objectification and sexualisation of the female body, specifically the Black female body.

As Nora Chipaumire suggested in 2014, the Black female body can acknowledge her own power and presence, and negotiate the way others look at it or see it in her own way, on her own terms.

Black female bodies are engaging in the freedom of expression as their own subjects, they are no longer mere objects.

Previous Post