I am a writer, playwright, and journalist with special interest in cultural and social politics.

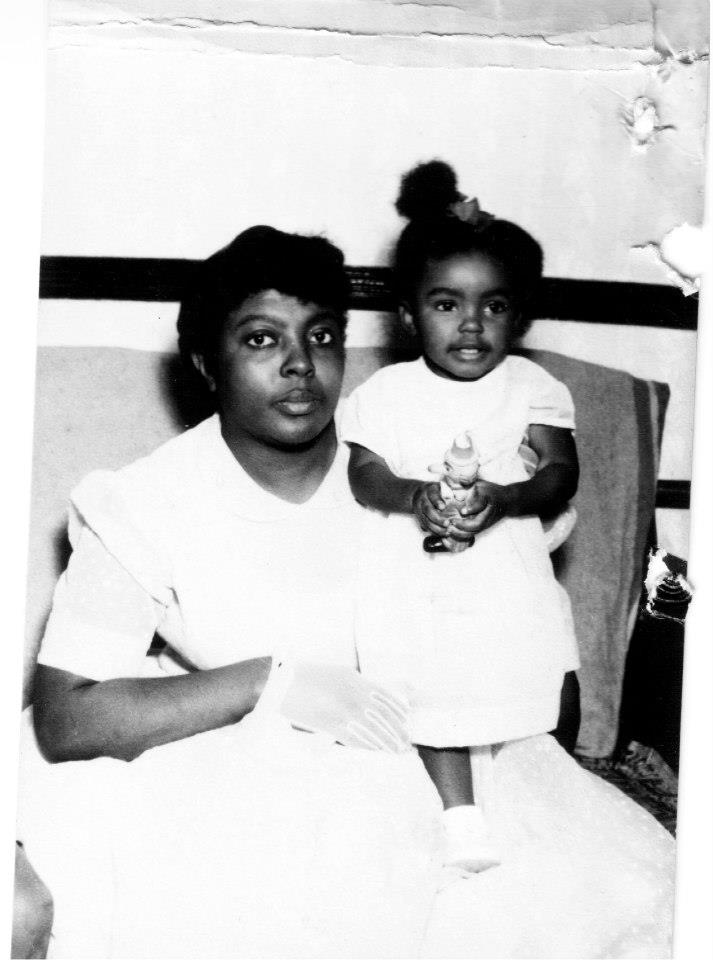

I was born in Wiltshire, England. A child of the 1960s. My parents were British citizens who had recently migrated from Jamaica in the Caribbean, and had chosen to settle in the countryside in the West of England; they hoped they would make new roots in a place that reminiscent of the lush areas of Jamaica that they had recently left. As it happened, my birth wasn’t solitary; they both had to be reborn with fresh identities in a new and foreign land. We all grew up together.

My reading and writing, from a very early age, was my salvation in a confusing world. My home life was a recreation of Jamaican behaviour and sensibilities, whilst my school life was as typically English as one could imagine. I was born learning to negotiate parallel identities to forge my way between my parents and the world.

Writing saved me from imploding.

It still does.

I was born in Wiltshire, England. A child of the 1960s. My parents were British citizens who had recently migrated from Jamaica in the Caribbean, and had chosen to settle in the countryside in the West of England; they hoped they would make new roots in a place that reminiscent of the lush areas of Jamaica that they had recently left. As it happened, my birth wasn’t solitary; they both had to be reborn with fresh identities in a new and foreign land. We all grew up together.

My reading and writing, from a very early age, was my salvation in a confusing world. My home life was a recreation of Jamaican behaviour and sensibilities, whilst my school life was as typically English as one could imagine. I was born learning to negotiate parallel identities to forge my way between my parents and the world.

Writing saved me from imploding.

It still does.

I am a writer, playwright, and journalist with special interest in cultural and social politics.

I was an Artist in Residence at Metal Culture Liverpool, 2019 – 2020; for my Time and Space residency I will be developing and workshopping a programme of plays with members of the refugee and migrant communities in Liverpool, and actors and directors for performances in June 2020 for Refugee Week.

I was short-listed for the International 15th Windsor Fringe Kenneth Branagh Award for New Drama Writing – 2018: Let Them Eat Cake.

I am the project leader and main creator of ‘The Talk’ Learning Resources produced in collaboration with Heart of Glass, and supported by Arts Council England.

I am a co-author of Sharing the Past, a book that has been collectively authored and edited by members of the Northamptonshire Black History Association (2008). It presents an overview of Northamptonshire’s connections to the wider world, and especially to Africa, the Caribbean and the Indian subcontinent.

From the introduction of Sharing the Past: “This book is about sharing the past for the sake of our shared future.“

As a previous Director of Northamptonshire Black History Association I was involved in the management of the organisation that won a national award from CILIP: Libraries Change Lives (2005).

I worked as a Research Assistant at the Oxford University School of Geography and the Environment where I assisted in the research and publication on a range of aspects of citizenship, cross-cultural fostering and adoption, and refugee migration in East and Central Africa.

I was a Writer-in-Residence for the Liverpool Independents Biennial Arts Festival (2018), and my work has been displayed at Tate, Liverpool on two occasions.

I have been published in the Guardian, the Northampton News and Herald, and WordsWords – a University of Northampton literary magazine.

Additionally, my articles, reviews and essays have been published in Art UK, Reader’s Digest, gal-dem, red pepper, Black Ballad, Cinema Femme, ROOT-ed Zine, and Metal Culture